COVID Crime: What Is Money Muling, and How Can We Fight It?

Money muling is one of the top pandemic-fuelled crimes, but there are ways to stop the mules

With temperatures frequently north of 100º, Arizona gets mighty hot in the summer. It turns out that during the summer of COVID-19, it’s also a hotbed of money muling, a criminal act that can be defined as:

The role of transferring stolen funds. Typically, money mules are unwittingly tricked into depositing a fraudulent check into a bank account or into receiving money from accounts without authorization of the account owner. In some cases, money mules know they are moving stolen funds and do so intentionally in exchange for receiving a portion of the money. The money mule moves stolen funds to a participant in the scam via an instant funds transfer or wire transfer, and the money is often unrecoverable and untraceable.

Criminals are targeting Arizona’s large elder population, cooped up in quarantine, to become money mules, exploiting victims’ loneliness and financial stress. In April, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) issued a bulletin warning that this crime is on the rise, and published a Money Mule Awareness Guide to help the public fight money mules.

Money Muling Is Here to Stay

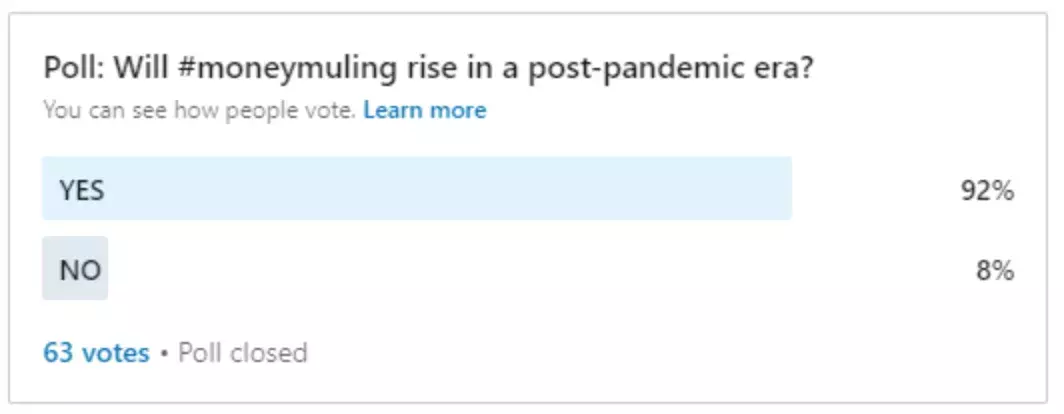

During the FICO Virtual Event this past May, we predicated that money muling would be one of the top scams being perpetrated during the pandemic. But I decided to dig a little further by reaching out to my network of payments and fraud professionals on LinkedIn to get their opinion. Were they expecting this crime to rise?

The response was a resounding “yes.” And we had some great comments as to the “why”:

- Transaction behaviors have evolved during the pandemic. Consumers are taking “mobile to the max” by using their phones for mobile deposit, contactless payments and person-to-person payments. In response, many banks in the US have raised daily limits on mobile check deposit to $7,500 per week, while online brokerages such as E*Trade allow customers to deposit $250,000 per day via mobile check deposit. Mobile deposit and money transfer, just two of the powerful features of today’s mobile banking apps, make it much easier for people to move money.

These fast, vast changes in deposit limits and transaction behaviors create opportunities for criminals looking to introduce ill-gotten funds into the legitimate banking system through money muling. Mobile-first banking will likely remain the “new normal”; The Wall Street Journal reports evidence that “customers will continue to pivot to digital banking” even after they feel more comfortable visiting businesses again. The Journal said about 85% of customers who have relied more on mobile and online platforms plan to continue doing so once the pandemic subsides, according to a survey from consulting firm Kearney.

- Ongoing economic stress will likely make more people susceptible to the siren song of money muling, which many folks don’t know can be both a federal and state crime. Romance scams, “make $100,000 from your kitchen table” scams and other cons can be made extremely compelling by cunning fraudsters.

The Intersection of Fraud and Money Laundering

Over the last few months I’ve talked a lot about the convergence of fraud and compliance infrastructure. The detection of money mule activity provides an excellent example of where to start. Here’s how fraud detection and anti-money laundering (AML) can work in concert:

- Money muling is often perpetrated by fraud networks, with a money mule “handler” directing the activity of a group of mules. In turn, multiple handlers can be orchestrated by a higher-ranking member of the criminal network.

- Banking behaviors typically associated with an individual mule — including higher-than-normal volumes of deposits and transfers — can trigger fraud alerts in a financial institution that has an enterprise-wide customer view, i.e., monitoring all an inflows, outflows, banking channels and devices down to the customer level. For example, a mule handler may sign into multiple mules’ accounts from a single device, which can be a suspicious activity.

- Suspected mules can be grouped into a cohort and compared with each other, and with persons and entities suspected of money laundering, using a link analysis solution such as FICO® Identity Resolution Engine. In this way, connections between mules, mule handlers and other members of a fraud network can emerge, giving financial institutions intelligence to move forward with in their investigations.

To fight money mules - a likely fixture in the post-pandemic world of financial crim -, it’s important for banks to start working today to improve their detection capabilities.

Check out my upcoming session on one of the methods to enhance detection as I join a panel of industry experts to talk about the realities of fraud and financial crimes convergence as well as how to get started at the Aite Financial Crimes Forum. Mark your calendars for Wednesday, September 16, from 10:30 - 11:15 AM for our discussion, Convergence of AML, Fraud, and Infosec: Is There a “There” There This Time Around?

Follow my latest thoughts on fraud, financial crime and the San Diego Padres on Twitter @FraudBird.

Popular Posts

Average U.S. FICO Score at 717 as More Consumers Face Financial Headwinds

Outlier or Start of a New Credit Score Trend?

Read more

Average U.S. FICO® Score at 716, Indicating Improvement in Consumer Credit Behaviors Despite Pandemic

The FICO Score is a broad-based, independent standard measure of credit risk

Read more

Average U.S. FICO® Score stays at 717 even as consumers are faced with economic uncertainty

Inflation fatigue puts more borrowers under financial pressure

Read moreTake the next step

Connect with FICO for answers to all your product and solution questions. Interested in becoming a business partner? Contact us to learn more. We look forward to hearing from you.